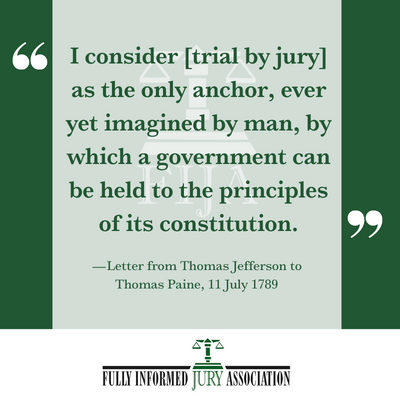

Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Thomas Paine

11 July 1789

The letter below is in the public domain and is reproduced as closely as possible to the version from which it was copied (at Founders Online), with one exception: bold and italic formatting has been added to highlight the section regarding jury rights.

Both Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine were seriously concerned with the French Revolution. The passage on jury rights in this letter from Jefferson to Paine expresses Jefferson’s concern that the revolutionary National Assembly in France, would not be convinced to adopt trial by jury. The letter is dated three days before the storming of the Bastille.

To Thomas Paine

Paris July 11. 1789.

Dear Sir

Since my last, which was of May 19. I have received yours of June 17. and 18. I am struck with the idea of the geometrical wheelbarrow, and will beg of you a further account if it can be obtained. I have no news yet of my Congé.

Tho you have doubtless heard most of the proceedings of the States general since my last, I will take up the narration where that left it, that you may be able to separate the true from the false accounts you have heard. A good part of what was conjecture in that letter is now become true history. A conciliatory proposition from the king having been accepted by the Nobles with such modifications as amounted to a refusal, the Commons voted it to be a refusal, and proceeded to give a last invitation to the clergy and nobles to join them, and to examine the returns of elections. This done they declared themselves the National assembly, resolved that all the subsisting taxes were illegally imposed, but that they might continue to be paid to the end of their present session and no longer. A majority of the clergy determined to accept their invitation and came and joined them. The king, by the advice of Mr. Necker, determined to hold a seance royale, and to take upon himself to decide what should be done. That decision as prepared by Necker was favorable to the Commons. The Aristocratical party made a furious effort, prevailed on the king to change the decision totally in favor of the other orders, and at the seance royale he delivered it accordingly. The Common chamber (that is the Tiers and majority of the clergy who had joined them) bound themselves together by a solemn oath never to separate till they had accomplished the work for which they had met. Paris and Versailles were thrown into tumult and riot. The souldiers in and about them, including even the king’s life guard, declared themselves openly for the Commons, the accounts from the souldiery in the provinces was not more favorable, 48. of the Nobles left their body and joined the common chamber, the mob attacked the Archbishop of Paris (a high aristocrat) under the Chateau of Versailles, a panick seised the inhabitants of the Chateau, the next day the king wrote a letter with his own hand to the Chamber of Nobles and minority of the Clergy, desiring them to join immediately the common chamber. They did so, and thus the victory of the Tiers became complete. Several days were then employed about examining returns &c. It was discovered at length that great bodies of troops and principally of the foreign corps were approaching Paris from different quarters. They arrived in the number of 25, or 30,000 men. Great inquietude took place, and two days ago the Assembly voted an address to the king for an explanation of this phaenomenon and removal of the troops. His answer has not been given formally, but he verbally authorised their president to declare that these troops had nothing in view but the quiet of the Capital; and that that being once established they should be removed. The fact is that the king never saw any thing else in this measure; [but those who advised him to it, assuredly meant by the presence of the troops to give him confidence, and to take advantage of some favorable moment to surprize some act of authority from him. For this purpose they had got the military command within the isle of France transferred to the Marshall de Broglio, a high flying aristocrat, cool and capable of every mischief.] But it turns out that these troops shew strong symptoms of being entirely with the people, so that nothing is apprehended from them. The National assembly then (for that is the name they take) having shewn thro’ every stage of these transactions a coolness, wisdom, and resolution to set fire to the four corners of the kingdom and to perish with it themselves rather than to relinquish an iota from their plan of a total change of government, are now in complete and undisputed possession of the sovereignty. The executive and the aristocracy are now at their feet: the mass of the nation, the mass of the clergy, and the army are with them. They have prostrated the old government, and are now beginning to build one from the foundation. A committee charged with the arrangement of their business, gave in, two days ago, the following order of proceedings.

‘1. Every government should have for it’s only end the preservation of the rights of man: whence it follows that to recall constantly the government to the end proposed, the constitution should begin by a Declaration of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man.

2. Monarchical government being proper to maintain these rights, it has been chosen by the French nation. It suits especially a great society; it is necessary for the happiness of France. The Declaration of the principles of this government then should follow immediately the declaration of the rights of man.

3. It results from the principles of monarchy that the nation, to assure it’s own rights, has yeilded particular rights to the monarch: the constitution then should declare in a precise manner the rights of both. It should begin by declaring the rights of the French nation, and then it should declare the rights of the king.

4. The rights of the king and nation not existing but for the happiness of the individuals who compose it, they lead to an examination of the rights of citizens.

5. The French nation not being capable of assembling individually to exercise all it’s rights, it ought to be represented. It is necessary then to declare the form of it’s representation, and the rights of it’s representatives.

6. From the union of the powers of the nation and king should result the enacting and execution of the laws: thus then it should first be determined how the laws shall be established, afterwards should be considered how they shall be executed.

7. Laws have for their object the general administration of the kingdom, the property and the actions of the citizens. The execution of the laws which concern the general administration requires provincial and municipal assemblies. It is necessary to examine then, what should be the organisation of the provincial assemblies, and what of the municipal.

8. The execution of the laws which concern the property and actions of the citizens call for a Judiciary power. It should be determined how that should be confided, and then it’s duties and limits.

9. For the execution of the laws and the defence of the kingdom, there exists a public force. It is necessary then to determine the principles which should direct it and how it should be employed.

Recapitulation.

Declaration of the rights of man.

Principles of the monarchy.

Rights of the nation.

Rights of the king

Rights of the citizens.

Organisation and rights of the national assembly.

Forms necessary for the enaction of laws.

Organisation and functions of the provincial and municipal assemblies

Duties and limits of the judiciary power.

Functions and duties of the military power.’

You see that these are the materials of a superb edifice, and the hands which have prepared them, are perfectly capable of putting them together, and of filling up the work of which these are only the outlines. While there are some men among them of very superior abilities, the mass possesses such a degree of good sense as enables them to decide well. I have always been afraid their numbers might lead to confusion. 1200 men in one room are too many. I have still that fear. Another apprehension is that a majority cannot be induced to adopt the trial by jury; and I consider that as the only anchor, ever yet imagined by man, by which a government can be held to the principles of it’s constitution.—Mr. Paradise is the bearer of this letter. He can supply those details which would be too lengthy to write.—If my Congé comes within a few days, I shall depart in the instant: if it does not I shall put off my voiage till the Equinox is over. I am with great esteem Dear Sir Your friend & servant,

Th: Jefferson

Source:

This letter is in the public domain and comes from Founders Online, part of the United States' National Archives.

-

Estimated Convictions Obtained by Plea Bargain

97%

-

Extra Punishment for Refusing a Plea Deal

64%

-

Rank of U.S. in Incarceration

1

-

Years FIJA Has Fought for Jury Rights

36