John Peter Zenger

Case Summary

seditious libel charges for printing true information about corrupt government officials

John Peter Zenger, a German immigrant, settled in New York with his family at the age of 13 in 1710. He spent his childhood as an apprentice to William Bradford learning the printing trade before setting up his own press in 1725.

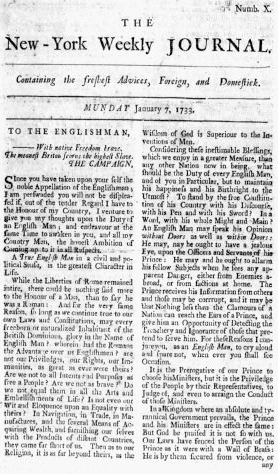

Zenger was approached by the political allies of the recently removed Chief Judge Lewis Morris to act as the printer for an independent newspaper. By late 1733 The New-York Weekly Journal was a huge success for the allies of Morris and enemies of the colony’s Governor William Cosby, who had summarily dismissed Morris for refusing to back his pension claims.

Immediately Cosby sought to take legal action against Zenger and his printing shop in retaliation against the newspaper that consistently lampooned the governor’s administration.

Despite having stacked the New York Courts with favorable magistrates as well as having selected each grand jury, Cosby failed in January and again in October of 1734 to attain the indictment of Zenger he sought.

Unable to work through the legal system to attain his desired end to the matter, Cosby sought to order the public burning of copies of the newspaper as a means of censoring Zenger’s publication. This, too, failed as the New York Aldermen, members of the municipal council, refused to permit it.

By November of 1734, a full year after the Weekly Journal’s first publication, Cosby resorted to proceed against Zenger through a highly unpopular legal procedure in the colony, which allowed the prosecution to bring charges without a grand jury indictment. Cosby’s stacked court subsequently issued a bench warrant for Zenger’s arrest.

On 17 November 1734, Zenger was jailed to await trial for seditious libel. With the bail set at £400, a huge sum for a printer, Zenger remained in jail for ten months awaiting his trial, while his wife faithfully published the newspaper rallying popular support.

At his arraignment in April of the following year, Zenger’s lawyers argued that the summary removal of Chief Justice Morris "at the Governor's pleasure" was improper. Unsurprisingly, the newly-appointed judges disagreed and disbarred Zenger’s lawyers for this assertion. Despite being an ally of Cosby, Zenger’s court-appointed lawyer, John Chambers, challenged the jury pool list twice and ensured Zenger would receive a generally fair jury. The trial date was then set for 4 August 1735.

During this period, Zenger’s allies were able to secure representation for him by the premier trial-lawyer in the colonies, Andrew Hamilton. Given the laws surrounding libel at the time, Hamilton's task was extremely difficult. The prosecution only had to prove that Zenger had printed the articles—not that what he printed was false.

It is important to understand that the legal concept of libel at the time was very different from what we understand it to mean now. At the time, the truth of the allegedly libelous statements was not only not a defense against the charges. Rather, it was an aggravating factor—something that was seen to increase the severity of the offense—because accusations against the government were all the more scandalous if, indeed, those accusations were true.

Jurors would be told that they were not allowed to interpret if the articles were libelous. Rather, this task was reserved for Cosby’s chief allies: the two judges overseeing the trial. This system guaranteed a verdict in favor of Cosby, because it did not matter whether the ‘libel’ was false or malicious, rather it only mattered that Zenger had published it. Chief Justice James DeLancey informed Hamilton on this matter clearly, arguing "You cannot be admitted, Mr. Hamilton, to give the truth of a libel in evidence."

Andrew Hamilton defending John Peter Zenger in court

On August 4th the trial began. As the prosecution brought up its witnesses to prove Zenger’s printing of the articles, Hamilton rose and stated that this was not necessary as Zenger admitted to printing the documents. The prosecution responded, after a period of silence, "As Mr. Hamilton has confessed the printing and publishing of these libels, I think the Jury must find a verdict for the king.” Chief Justice DeLancey reinforced this direction with the order that the jurors must find Zenger guilty of libel as he admitted to publishing the articles.

It is important to understand that the legal concept of libel at the time was very different from what we understand it to mean now. At the time, the truth of the allegedly libelous statements was not only not a defense against the charges. Rather, it was an aggravating factor—something that was seen to increase the severity of the offense—because accusations against the government were all the more scandalous if, indeed, those accusations were true.

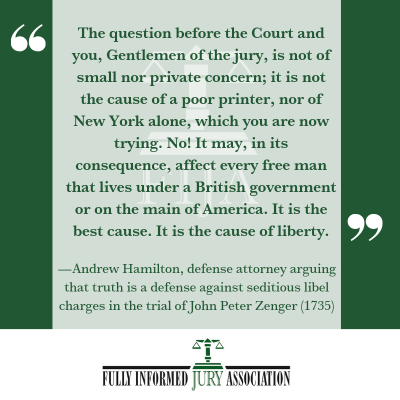

Hamilton, in his lengthy summation to the jury, responded to these orders by way of arguing jury nullification stating:

I know, may it please Your Honor, the jury may do so. But I do likewise know that they may do otherwise. I know that they have the right beyond all dispute to determine both the law and the fact; and where they do not doubt of the law, they ought to do so. Leaving it to judgment of the court whether the words are libelous or not in effect renders juries useless (to say no worse) in many cases.

Following the unexpected turn towards nullification, the Chief Justice reminded the jury of his orders to return a guilty verdict and the explicitness of the law on this point. Deliberating for only 10 minutes, the jury returned a ringing verdict of not guilty. Calls for order by the Chief Justice were drowned out by the "shouts of joy" with DeLancey ultimately leaving “the courtroom to the jubilant crowd."

While it is clear the trial started on 4 August, different sources report that Zenger was acquitted either on 4 or 5 August 1735. Having yet to find definitive historic source material, we commemorate this acquittal on 5 August as reported by law professor Douglas O. Linder and the Jacob Burns Law Library of George Washington University,

The trial narrative and later documents about the trial reveal a jury completely unwilling to enforce the law or the judge’s orders in one of the earliest American examples of jury nullification.

Zenger’s acquittal indisputably influenced the First Amendment and history of jury nullification in America. Stephen D. Solomon writes in his book Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech:

After the jury's verdict, popular resistance to libel charges brought by royal authorities seemed like too perilous a sea for prosecutors to navigate. In the late 1760s in Boston, as the Sons of Liberty opposed British measures infringing on the liberties of colonists, grand jurors resisted repeated attempts to indict the radical publishers of the Boston Gazette... Indeed, from the Zenger case until independence, common law cases against dissidents all but disappeared.

Case Documents

Other Resources

- The New-York Weekly Journal

- Solomon, Stephen D., Revolutionary Dissent: How the Founding Generation Created the Freedom of Speech

- Miller, Eugene F., Introductory Note to A Brief Narrative of the Case and Tryal of John Peter Zenger

- Linder, Douglas, The Trial of John Peter Zenger: An Account

- Old New York, A Journal Relating to the History and Antiquities of New York City

Research and Writing Credit: Nathan Tschepik, Kirsten C. Tynan

Photo Credit: The New-York Weekly Journal and Andrew Hamilton Defending John Peter Zenger from Wikimedia Commons

-

Estimated Convictions Obtained by Plea Bargain

97%

-

Extra Punishment for Refusing a Plea Deal

64%

-

Rank of U.S. in Incarceration

1

-

Years FIJA Has Fought for Jury Rights

36